U.S. Inks Deal to Build New Military Bases that Can Serve as Launching Point For Attacks on Yemen and Potentially Iran

originally published at CovertAction Magazine

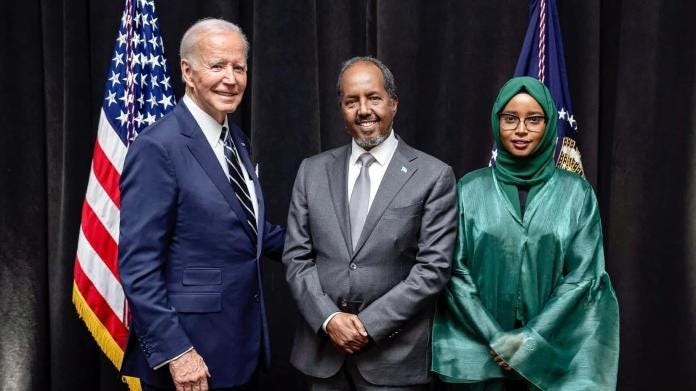

U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs Mary Catherine (“Molly”) Phee, Chargé d’Affaires to the U.S. Embassy Shane Dixon, Defense Minister Abdulkadir Mohamed Nur, and President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud attend the signing of a security pact in Mogadishu, Somalia, on February 15, 2024. [Source: voanews.com]

On February 15, the Biden administration signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the Government of Somalia to construct up to five military bases for the Somali National Army in the name of bolstering the army’s capabilities in the ongoing fight against the militant group al-Shabaab.

According to statements by U.S. officials, the bases are intended for the Danab (“Lightning”) Brigade, a U.S.-sponsored special operations force that was established in 2014.

This force has been linked to repeated incidents of brutality, according to a Somali newspaper, including one near the village of Shanta Barako in Lower Shabelle, where U.S. troops were present when two civilians were killed.

Danab operates out of Baledogle, a Soviet-built airport about 100 kilometers north of Mogadishu, which was reconstituted as a U.S. military base in 2012, and is host to one of the largest concentrations of U.S. troops in Africa, behind only bases in Djibouti and Niger.

Funding for Danab initially came from the U.S. State Department, which contracted the private security, i.e., mercenary, firm Bancroft Global[1] to train and advise the unit, though more recently it has received funding, equipment and training from the Department of Defense under the the classified 127e program.

The latter is a U.S. budgetary authority that allows the Pentagon to bypass congressional oversight by allowing U.S. special operations forces, described in Foreign Policy magazine as some of the American military’s most highly trained killers, to use foreign military units as surrogates in counter-terrorism missions.

According to the Council on Foreign Relations, the U.S. provided several billion dollars to train and equip the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) and Somali security forces between 2012 and 2022.[2]

Samar Al-Bulushi and Ahmed Ibrahim reported in Responsible Statecraft that “the U.S. government’s plan to train Somali security forces at newly-established military bases in five different parts of the country (Baidoa, Dhusamareb, Jowhar, Kismayo, and Mogadishu) is a back-door strategy not only to expand the U.S. military’s presence in Somalia, but to position itself more assertively vis-à-vis other powers in the region.”

The Mogadishu-based Nova news service reported that the U.S. has “positioned the Eisenhower aircraft carrier in the Gulf of Aden and Somalia could offer the Biden government a strategic position for the missions launched to combat the Houthis, the pro-Iranian Shiite rebels who are giving Israeli ships [and Westerners] a hard time in the Red Sea.”

The new military bases in Somalia could be used as a launching pad for threatened U.S. aggression against Iran, which neo-conservatives in Washington have long desired.

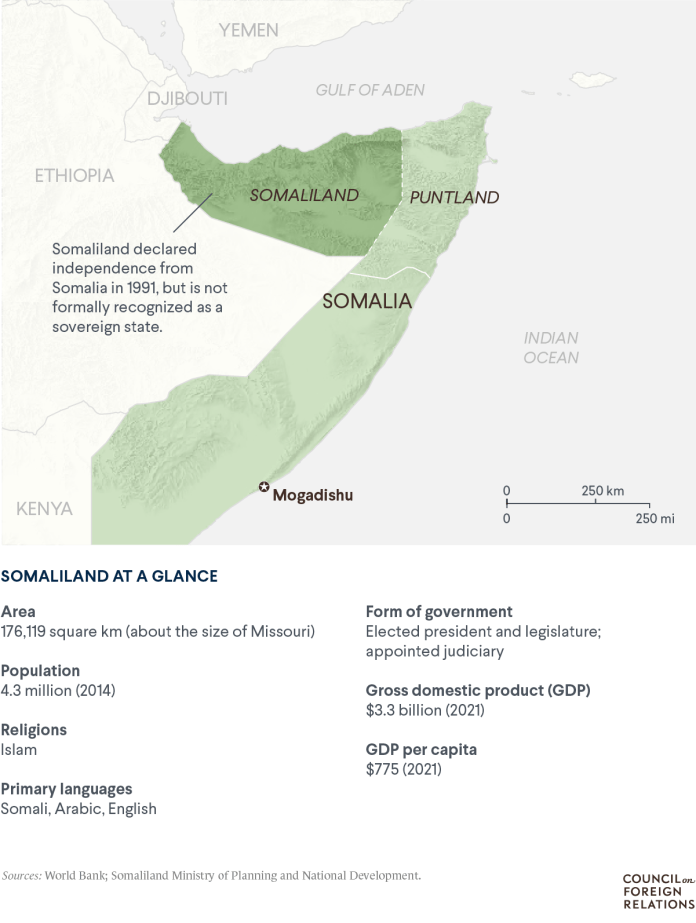

Under the terms of the February MOU, Somaliland, which has been trying to secede from Somalia since 1991 but has not been recognized by any UN member-state, would lease 20 acres of Gulf of Aden seacoast to Ethiopia to build a commercial port and naval base in exchange for Ethiopia’s recognition of Somaliland as an independent state.

Washington neo-conservatives have called for recognizing Somaliland so the U.S. would not have to deal with a secessionist state in its plans to re-establish Berbera, a military base first established by the U.S. in the 1980s that was taken over by the Soviets and then abandoned.

In September 2022, then-AFRICOM Commander Stephen Townsend visited with secessionist leaders in Somaliland; he was the highest military official to visit the area and lend prestige to the separatist movement.[3]

The Berbera base in Somaliland would be another U.S. military base in the Horn that could be used as a launching point for military interventions in the Middle East.[4]

Expanding Network of Bases

CovertAction Magazine has previously reported on a widening network of U.S. military bases in both Africa and the Middle East to which the new Somali bases are a significant addition.

In August, two months before the Tribe of Nova Music Festival massacre in Israel, the Pentagon awarded a $35.8 million contract to build U.S. troop facilities for a secret base it maintains deep within Israel’s Negev Desert, just 20 miles from Gaza, code-named “Site 512.”

Procurement records describe the secret base, located off Mt. Qeren, as a “life support area,” typical of the kind of language the Pentagon uses for U.S. military sites that it wants to conceal.

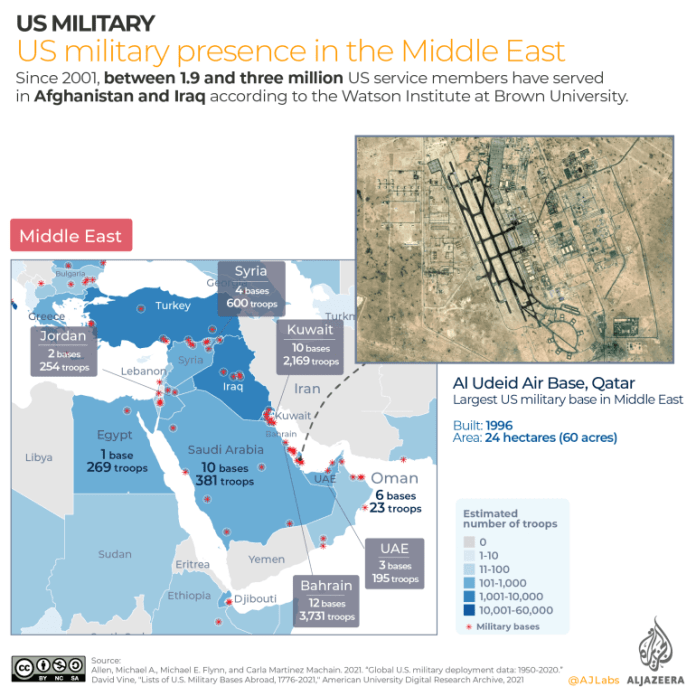

The largest U.S. military base in the Middle East—the Al Udeid Air Base—is west of Doha, the capital of Qatar. It hosts the U.S. Air Force Central Command, which coordinates U.S. bombing operations in Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan and elsewhere, and some 11,000 U.S. military personnel.

Construction of the $60 million facility, which the Air Force says “resembles the set of a futuristic movie,” was completed in 2003.

The U.S. currently hosts at least 10 military bases in Saudi Arabia, according to a 2021 report by Al Jazeera. Additionally it hosts 10 bases in Kuwait, 12 bases in Bahrain, at least 12 bases in Iraq, six bases in Oman, two bases in Jordan, four bases in Syria, two bases in Turkey, one in Egypt, and three bases in the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

According to Al Jazeera, the U.S. hosts 3,731 of its troops in Bahrain, 2,169 in Kuwait, 2,500 in Iraq, and 600 in Syria. Overall, the U.S. has 40,000 troops stationed across the Middle East, according to Axios, and, on October 31, announced the deployment of an additional 900 troops to the region.

CovertAction Magazine has previously reported on the Biden administration’s efforts to establish drone bases in Ghana, Ivory Coast and Benin after a coup in Niger jeopardized a $110 million base the U.S. considered to be the “largest Airman built project in U.S. Air Force history.”

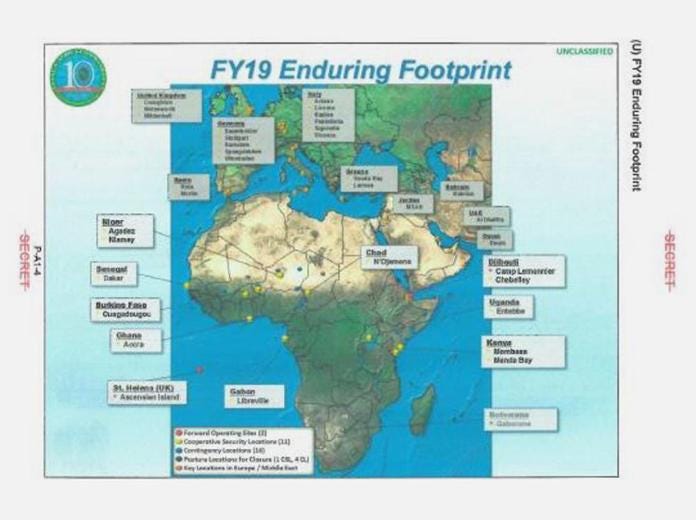

In February 2020, journalist Nick Turse reported that a secret AFRICOM map showed a network of 29 U.S. military bases stretching from one side of Africa to the other.

U.S. Special Operations forces at the time were deployed in 22 African countries: Algeria, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Chad, Côte D’Ivoire, Djibouti, Egypt, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Libya, Madagascar, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Somalia, Tanzania and Tunisia.[5]

The 29 U.S. military bases were located in 15 different countries or territories, with the highest concentrations in the Sahelian states on the west side of the continent, as well as the Horn of Africa in the northeast.

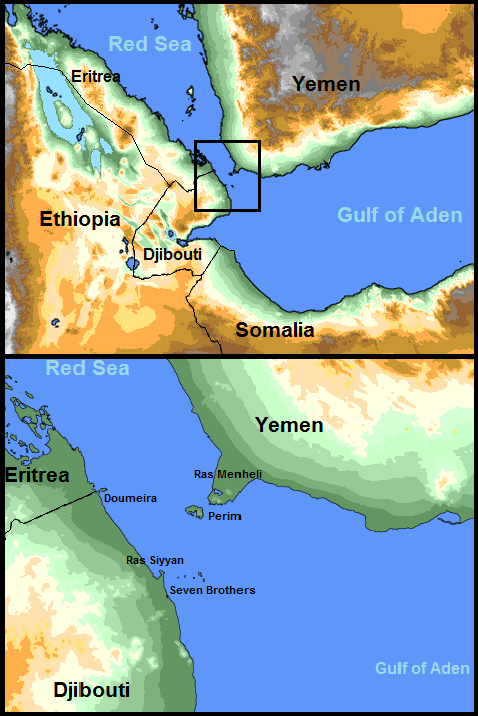

The latter’s strategic importance was outlined years ago by General Norman Schwarzkopf, commander of U.S. military operations in the first Persian Gulf War, who noted that “the Red Sea, with the Suez Canal in the North [of the Horn] and the Bab-el-Madeb in the South, is one of the most vital sea lines of communication and a critical shipping link between our Pacific and European allies.”[6]

Up to $700 billion in maritime shipping passes by Somalia every year, encompassing nearly all trade between Europe and Asia, so U.S. control of the region is imperative.

Another Secret U.S. Dirty War

Since 2007, the U.S. has been fighting a secret dirty war in Somalia involving hundreds of air attacks and commando raids that has accentuated rather than diminished the threat of terrorism.

The Washington Post reported in July 2022 that al-Shabaab was “resurgent,” while a Pentagon think tank, the Institute for Defense Analysis (IDA), called al-Shabab “the largest and most kinetically active al-Qaeda network in the world.”[7]

The IDA concluded that America’s nascent war in the Horn of Africa was plagued by a “failure to define the parameters of the conflict” and “an overemphasis on military measures without a clear definition of the optimal military strategy.”

Despite these problems and the ruinous effects of the war for Somalians, the Biden administration expanded U.S. involvement by redeploying 450 U.S. Special Forces troops that Donald Trump had withdrawn. Biden also announced an increase in military aid to the Somali army last winter.

The Trump administration had escalated the war by asking for parts of Somalia to be declared an “area of active hostilities,” allowing the U.S. military to employ looser war-zone targeting despite the lack of a congressional declaration of war. This resulted in a tripling of bombing attacks, which increased by 460 percent from Obama’s presidency.

So far in 2024, the U.S. Africa Command has conducted at least seven air strikes in Somalia, targeting al-Shabaab.

Nick Turse reported in The Intercept on a U.S. drone strike in March 2018 that killed a 22-year-old woman, Luul Dahir Mohamed, and her 4-year-old daughter, Mariam Shilow Muse. An investigation found that the attack was the product of faulty intelligence, and rushed and imprecise targeting by a Special Operations strike cell whose members were inexperienced.[8]

High civilian casualty totals in Somalia have stemmed in part from the fact that the Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC)-led unit responsible for drone attacks in Somalia, Libya and Yemen have competed to produce high body counts.

Chilling detail on the dirty war in Somalia was provided by Jeremy Scahill in his 2012 book Dirty Wars. He shows how the U.S. helped to create al-Shabaab by supporting a brutal Ethiopian invasion of Somalia in 2006-2007. Al-Shabaab emerged at the vanguard in the fight against foreign occupation.[9]

The Bush administration had spurned a peace overture by Somali leader Sharif Sheik Ahmed of the Union of Islamic Courts (UIC), who offered to cooperate with the U.S. in fighting terrorism.

The Bush and Obama administrations subsequently empowered brutal warlords, paid off by the CIA, who adopted a kill-and-capture campaign targeting al-Shabaab leaders that resulted in the assassinations of Imams and several school teachers.[10]

General Yusuf Mohammed Siad (aka Indha Adde), a drug and weapons trafficker who had helped destroy Somalia in the 1990s, was one of the CIA’s favorites. He earned the nickname “the butcher” after violently taking over Somalia’s Lower Shabelle region.[11]

Adde stated that “America knows war. They are war masters….They are teachers, great teachers.”[12]

Somalia’s current president, Hassan Sheikh Mohamud was helped by the Biden administration in winning May 2022 elections according to Dr. Abdiwahab Sheikh Abdisamad, executive director of the Institute for Horn of Africa Studies.

Mohamud had been Somalia’s president from 2012 to 2017, during which time journalists were executed by firing squad. He was accused by a UN monitoring group of giving weapons to clan militias and al-Shabaab, and conspiring with a U.S. law firm (Shulman Rogers) to steal overseas assets that had been recovered by the Somali Central Bank.

The UN Monitoring Group said the information it had gathered as of July 15, 2014, “reflect[ed] exploitation of public authority for private interests [under Mohamud] and indicates at the minimum a conspiracy to divert the recovery of overseas assets in an irregular manner.”

This latest base agreement exemplifies how U.S. imperial ambitions routinely lead to close alliance with horrendous leaders whom most Americans would not want to support with their taxpayer dollars if they knew what was going on.

Besides the granting of basing rights, the U.S. supports Mohamud because of his friendliness toward U.S. oil investors in Somalia, considered a “new frontier for hydrocarbon exploration,” which possesses the largest untapped reserve of oil and longest unexplored coastline in Africa.

In October 2022, Mohamud’s government signed a $7 million oil exploration agreement with Texas-based Coastline Exploration, despite the opposition of the Financial Governance Committee, a group of experts comprised of the Somali finance minister, parliamentarians, and World Bank members who warned against signing any oil deals because the country lacked a legal framework to protect its own interests.[13]

The destructiveness of U.S. policies in Somalia makes clear the need for an anti-imperialist movement in the U.S., modeled potentially after the anti-imperialist league of the early 20th century, that demands a systemic transformation of U.S. foreign policy.

The new anti-imperialist movement should recognize the U.S. as an heir to the British empire, whose military base network is a relic from a past age. It spawns violence around the world and is antithetical to the growth of real democracy.

Bancroft’s founder, Michael Stock, a great grandson of a partner in the legendary banking firm Kuhn, Loeb & Co., had invested in a luxury hotel in Somalia sprawled across 11 acres of rocky white beach. Stock’s most prized employee, Richard Rouget, had been the right-hand man of Bob Denard, a notorious agent of French colonialism who backed four coups in the Comoros Islands and was suspected of involvement in the murder of two leading anti-apartheid activists with the African National Congress (ANC). Jeremy Kuzmarov, Obama’s Unending Wars: Fronting the Foreign Policy of the Permanent Warfare State (Atlanta: Clarity Press, 2019), 94. ↑

Besides the Danab brigade, these surrogates include the Puntland Security Force that was built by the CIA and mentored by U.S. Navy Seals before it was transferred to Somali military control. According to a report in Vice Magazine, the U.S., in creating the Puntland Security Force, empowered a single family dynasty, the “Dianos,” who directed the militia for three generations. When Donald Trump removed U.S. troops from Somalia, the Puntland Security Force devolved into factionalism and began fighting itself, killing civilians along the way. ↑

“Top U.S. Military Official Visits Somaliland Amidst Growing Interest in Berbera,” Somaliland Reporter, March 13, 2022. ↑

The neo-cons also want to cultivate relations with an independent Somaliland so they can exploit offshore oil and gas deposits. ↑

Turse wrote: “From north to south, east to west, the Horn of Africa to the Sahel, the heart of the continent to the islands off its coasts, the U.S. military is at work. Base construction, security cooperation engagements, training exercises, advisory deployments, special operations missions, and a growing logistics network, all undeniable evidence of expansion—except at U.S. Africa Command [which had tried to minimize the U.S. footprint in Africa].” ↑

David N. Gibbs, “Realpolitick and Humanitarian Intervention: The Case of Somalia,” International Politics, March 2000. ↑

Nick Turse reported in The Intercept that “in addition to a 22 percent rise in fatalities from terrorism in Somalia from 2022 to 2023, violence has increasingly bled across the border into Kenya which saw deaths from al-Shabab attacks double over the same span.” On March 16, The New York Times reported on a brazen al-Shabab attack on a hotel near Somalia’s parliament, resulting in three deaths and 27 injuries. ↑

The Merchants of Death war crimes tribunal, an effort by peace activists to hold weapons manufacturers accountable for war crimes, showed that a drone missile made by Lockheed unleashed on Somalia struck farmers in a small village north of Mogadishu who were digging an irrigation canal in the middle of the night. Another U.S. drone strike killed a prominent businessman, Mohamud Salad Mohamud in Jilib, a city in middle Juba, while another killed an 18-year-old girl and her two sisters and grandmother in Jilib after their home was struck while they were eating dinner. ↑

Jeremy Scahill, Dirty Wars: The World Is a Battlefield (New York: Nation Books, 2012), 225. ↑

Scahill, Dirty Wars, 127, 128. ↑

Scahill, Dirty Wars, 191. ↑

Scahill, Dirty Wars, 201. ↑

Kenyan MP Farah Maalim accused President Mohamud of auctioning his country’s oil and gas resources, stating: “There must be a legal regime that mandates Parliamentary approval for all & any contract on natural resources. Profit sharing agreement on oil & gas must be conducted in the open,” he tweeted. “Somalia sadly turned into another Angola today. President Hassan signed off Somali oil/gas.” ↑