[Source: upi.com]

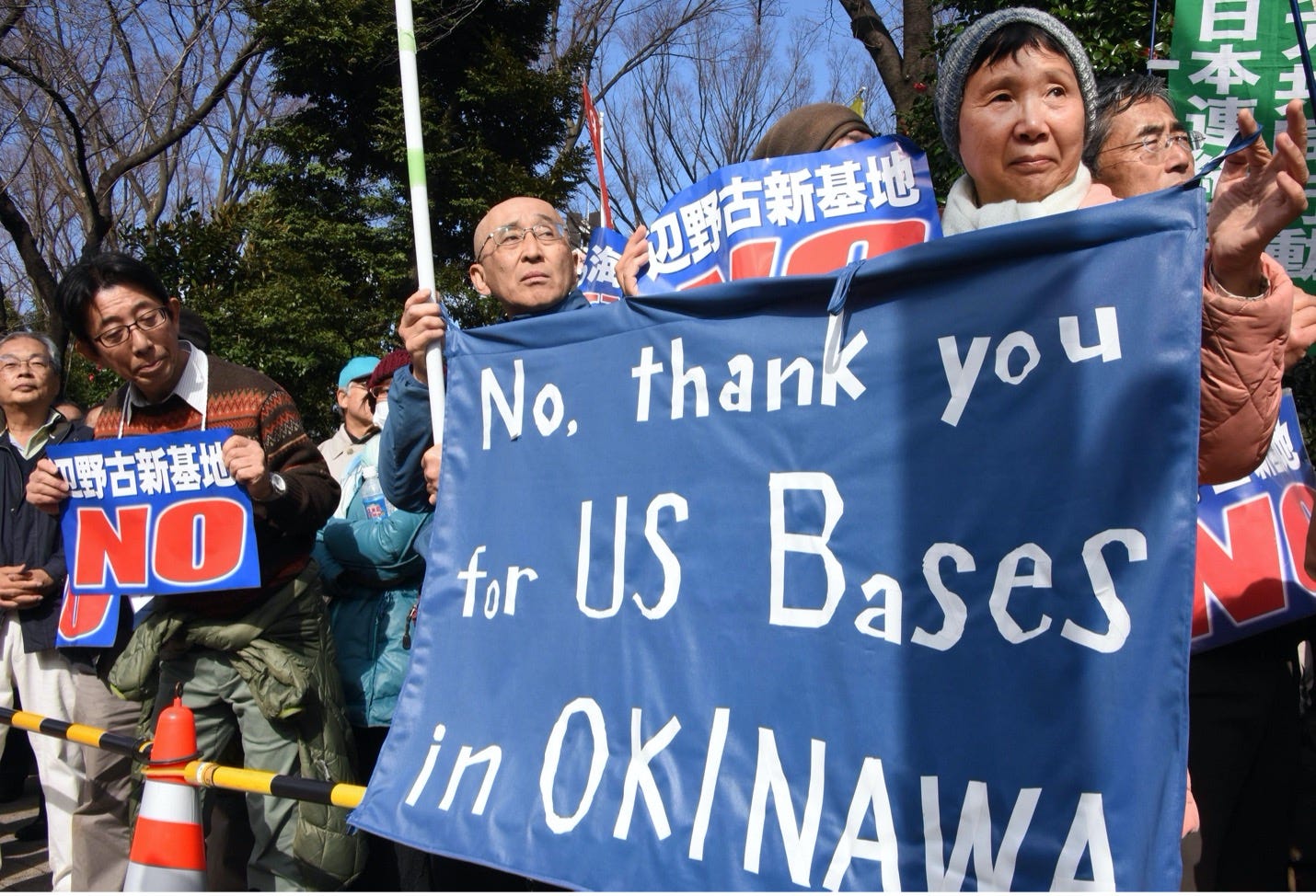

On August 12, 2024, around 2,500 Okinawans including the island’s governor staged a demonstration near Marine Corps Air Station Futenma.

The main focus of the protest—organized by the anti-U.S. military political party All Okinawa and two civic groups fighting in the courts to eliminate base aircraft noise—was a rash of sexual assaults allegedly committed against local women by U.S. servicemen stationed at the base.

In March, a senior airman, Brennon R.E. Washington was indicted on charges of kidnapping and sexually assaulting a minor. In June, prosecutors indicted Marine Lance Cpl. Jamel Clayton on attempted sexual assault charges.

All Okinawa co-chairman Susumu Inamine, a former mayor of Nago city, told the crowd that the Japanese government had been hiding information regarding these and other cases, and that even Okinawa’s governor was kept in the dark, which, she said, was “unforgivable.” Other speakers at the rally condemned the recent return of Bell Boeing MV-22 Osprey flights over the island, which are known for making a lot of noise.

Rally in Ginowan city, Saturday, Aug. 10, 2024. [Source: stripes.com]

Claudia Junghuyn Kim, a professor of international affairs at City University of Hong Kong, is author of a new book called Base Towns: Local Contestation of the U.S. Military in Korea and Japan (New York: Oxford University Press, 2023) that details a long pattern of protests directed against U.S. military bases in the Far East.

Kim carried out extensive research on the anti-base protest movement, participating in many anti-base protests. One of the more inspiring ones occurred in 2014 near the South Korean city of Pocheon, outside the largest American firing range in Asia, where normally conservative farmers climbed up a mountain to act as voluntary human shields against shooting exercises and placed straw bales at locations surrounding the base and set them ablaze as they threatened to occupy the base, block its gate with farm tractors, and suspend water supplies.[1]

[Source: academic.oup.com]

Kim observes that during the 1960s through the 1980s base protests were usually led by left-wing groups, including South Koreans demanding the removal of the bases as a precondition for the reunification of North and South Korea.

May 22 was designated as “Anti-American Day” because of U.S. support for the 1980 Kwangju massacre, where the South Korean dictatorship led by Roh Tae Woo massacred pro-democracy protesters. A popular protest song titled “Song For the USFK Withdrawal” proclaimed: “The Japs were expelled, and the Yankees came…we’ll wipe you out and march toward unification.”[2]

Japanese protesters portrayed the U.S. military presence as a betrayal of the spirit of Japan’s post World War II pacifist constitution and violation of its sovereignty.

In Okinawa, a U.S. colony from 1952 to 1972, bases became a symbol of foreign imperial occupation and a trigger for pro-independence activists, who in the 1970 Koza riot set fire to American military vehicles and raided Kadena air base.[3]

Scene from 1970 Koza riot in Nago, Okinawa. [Source: alchetron.com]

In more recent years, Kim finds that most anti-base protests in South Korea and Japan have focused primarily on the negative environmental ramifications of U.S. military bases, and problem of noise from U.S. live fire exercises or Air Force training.

They also protest against the sexual assaults of local women by U.S. soldiers, as in the Futenma protest, and emphasize that the bases take up choice local land.

Some of the protesters have sought to distance themselves from leftist groups because they feel they can gain more support from the wider community by focusing on local concerns rather than on geopolitics. They are weary of alienating themselves from local politicians and facing societal stigmatization in a political climate that is similar to the McCarthy-era in the U.S.

An annual South Korean poll between 2012 and 2019 showed support for the U.S. military presence ranging from 67 to 82 percent. Japanese polls also show acceptance of U.S. military bases, with some policy-makers alleging that the anti-base protesters are “on the Chinese payroll.”[4]

Kim writes that even setting aside the issue of the U.S. military, there is an aversion among the Japanese public for social movements, which some allege borders on phobia, making it difficult for the anti-base movement to expand.

Postwar security has been linked to the U.S. presence and growing military ambitions are synchronized with U.S. regional strategy.

In South Korea, the government legitimizes the existence of the U.S. bases by suggesting that the U.S. military helps to safeguard the country from the North Korean “threat.” Politicians remain “faithful to the American presence that they associate with security and prosperity,” Kim writes.[5]

Rodriguez live fire base near the North Korean border which inspired protests in 2014 where farmers used their bodies as human shields. [Source: apjjf.org]

When provincial or municipal government officials support the anti-base protesters, they often do so in order to gain financial concessions from Tokyo and Seoul. In this way, Kim suggests that local elite support for the anti-base movement can be a double-edged sword that results in the cooptation of the movement because the end goal is not actually the removal of the bases.

A major impediment to the growth of the base movement is the revenue that bases generate for local businesses and money that the federal governments in Korea and Japan will pump into communities that host bases in order to effectively buy off its people.

This is very similar to the situation in the U.S., where military bases are strategically placed in rural areas where they can provide an economic stimulus and local politicians end up lobbying against base closures because it would ruin the local economy.[6]

[Source: apjjf.org]

The U.S. acquired a vast array of military bases in Korea and Japan as a spoil of the Pacific and Korean Wars. In Korea, many of the bases were taken over from the Japanese colonizers.[7]

Today, the U.S. military has 83 military installations in South Korea and 121 installations in Japan, occupying hundreds of thousands of acres of choice land.[8]

These figures contradict official histories in the U.S. taught to school children suggesting that the U.S. waged the Pacific and Korean Wars for altruistic and defensive purposes.

In reality, a key motive, laid out at the time by General Douglas McArthur, was to esablish a chain of military bases from the Ryukyus (Okinawa) to the Aleutian islands, from which the U.S. could take over from the European powers in dominating Southeast Asia while securing access to its rich mineral resources.

General Douglas McArthur [Source: britannica.com]

Over the decades, the U.S. used all kinds of skullduggery to help impose client leaders who were acquiescent to U.S. designs and would suppress left-wing movements that wanted to expel the U.S. military base network.

In Japan, the Public Safety branch of the U.S. military occupation authority from 1945-1952 mobilized Japanese police to suppress the Japanese Communist Party.[9] The CIA subsequently financed the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), which favored close integration with the U.S. during the Cold War along with a conservative economic program.[10]

In 1960, Japanese Prime Minister Kishi Nobosuke, the “Monster of Showa” who had overseen sadistic medical experiments on Chinese prisoners of war in World War II, signed a security deal with the U.S. that allowed the U.S. to retain its military bases in Japan indefinitely, paving the way for the situation today.[11]

Anti-US-Japan Security Treaty Protesters in 1960. [Source: tofugu.com]

Japanese Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi, center, shakes hand with Senator Prescott Bush, father of George H.W. Bush, as President Dwight D. Eisenhower looks on at Burning Tree Country Club in Greenwich, Connecticut, in 1957. [Source: nbcnews.com]

The CIA infiltrated the militant public sector trade union, Sohyo, the main organizing arm of the Japanese Socialist Party, which was against the base deal.[12]

This history is relevant in helping to understand the relative political timidity of the anti-base movement today in Japan, which is a legacy of the Cold War and CIA’s collaboration with local elites in crushing Japan’s once vibrant anti-imperialist and socialist left.

A similar pattern is at play in South Korea, where the CIA created the Korean CIA to empower right-wing leaders like Syngman Rhee (1945-1960) and Park Chung Hee (1960-1979), who supported a vast U.S. military presence in South Korea and accepted U.S. support in crushing the political left, which strove for Korean national reunification.

Syngman Rhee, left, Park Chung-Hee, right. [Source: jegvillesverden.blog]

South Korea’s political landscape turned more to the right in 2014 after the disbanding of the Unified Progressive Party (UPP), which had functioned as a “bastion of leftist-nationalist politics.”[13]

Surviving elements of the anti-imperialist left in both South Korea and Japan have found common cause with right-wing nationalists who resent the emasculating effect of having a foreign military presence in their country.

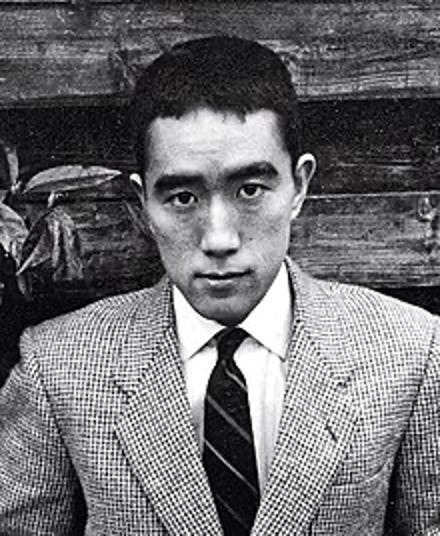

In Japan, a right-wing writer, Mishima Yukio committed suicide in 1970 after giving a speech suggesting that Japan’s Special Defense Force should become a “national military” and “break out of the U.S. hegemony.”[14] These comments make clear a wide unease with Japan’s function as an adjunct of U.S. power in Southeast Asia, across the political spectrum.

Mishimo Yukio [Source: en.wikipedia.org]

U.S. military bases are least popular in Okinawa, which was turned in the 1950s into “one continuous American base,” in the words of an American diplomat. Okinawa today houses 33 military installations on 46,229 acres of land, 70 percent of land used by the U.S. military throughout Japan.[15] Kim writes of an annual peace march in Okinawa and popularity of anti-base politicians like Inamine Susumu, Nago’s mayor from 2010 to 2018, and Otaga Takeshi.[16]

[Source: japantimes.co.jp]

In 2010, President Barack Obama forced the resignation of Japanese Prime Minister Hatoyama Yukio when he opposed an agreement that had been illegally rammed through the Japanese diet by his predecessor mandating the relocation of the Henoko air station in Okinawa.

According to historian Gavan McCormack, Hatoyama’s capitulation was considered a “day of humiliation for the Rykuyus akin to that of April 1952 when the islands were offered to the U.S. as part of a deal for the restoration of Japanese sovereignty [from U.S. military occupation].”[17]

Hatoyama Yukio [Source: youtube.com]

These comments illustrate the injustice underlying the U.S. military base network that has resulted in continued protest over the decades.

That protest sadly has not extended very much to the U.S. itself because most Americans are oblivious as to the local consequences of U.S. military bases, which goes unreported in U.S. media. Peace activists are often concerned primarily with the latest military escalation rather than on trying to dismantle the structure of the American empire that enables the forever wars and human carnage associated with them.

[1] Claudia Junghuyn Kim, Base Towns: Local Contestation of the U.S. Military in Korea and Japan (New York: Oxford University Press, 2023), 1.

[2] Kim, Base Towns, 163. USFK stands for U.S. Forces Korea. In the 1980s, South Korean university students organized a movement to resist mandatory military training, stating they did not want to serve as “mercenaries for Yankees.” One student group was called “U.S. Imperialists’ Military Base-ification of the Korean Peninsula.” A 1986 protest song warned of a ‘nuclear storm” threatening “national survival” and cried out, “antiwar, anti-nuke, Yankee go home!.”

[3] Kim, Base Towns, 40. In 1972, Okinawa reverted to Japanese control under a deal struck by the Nixon administration in which Japan agreed to allow for the maintenance of U.S. military bases in Okinawa.

[4] Kim, Base Towns, 45. Anti-base protesters in Okinawa are maligned for allegedly helping to carry out a scheme to boost Chinese influence, in part because the administration over the disputed Senkaku and Diayou islands lies with the Okinawa city of Ishigaki.

[5] Kim, Base Towns, 45.

[6] See Joan Roelefs book, The Trillion Dollar Silencer: Why is There So Little Anti-War Protest in the United States (Atlanta: Clarity Press, 2023).

[7] Kim, Base Towns, 15.

[8] Kim, Base Towns, 13.

[9] See Jeremy Kuzmarov, Modernizing Repression: Police Training and Nation Building in the American Century (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012), ch. 3.

[10] Michael Schaller, America’s Favorite War Criminal: Kishi Nobusuke and the Transformation of U.S.-Japan Relations (Japanese Policy Research Institute, July 1995). The secret funds were allegedly obtained from the sale of rare metals and diamonds that had come under allied control at the end of World War II and looted gold seized under the oversight of Air Force General Edward Lansdale, an Office of Strategic Services (OSS) propagandist and legendary CIA operative.

[11] Schaller, America’s Favorite War Criminal.

[12] Brad Williams, “US Covert Action in Cold War Japan: The Politics of Cultivating Conservative Elites and Its Consequences,” Journal of Contemporary Asia, 50, 4 2020, 593-617.

[13] Kim, Base Towns, 44.

[14] Kim, Base Towns, 39.

[15] Kim, Base Towns, 17, 33.

[16] Kim, Base Towns, 133.

[17] Jeremy Kuzmarov, Obama’s Unending Wars: Fronting the Foreign Policy of the Permanent Warfare State (Atlanta: Clarity Press, 2019), 209, 210.